Plant-based diets offer one of the most effective means of reducing our environmental impact. Aron Penczu takes an in-depth look at the future of the meat industry, from smallholder farming to meat and dairy taxes and culturing meat. Though transformation is possible, he argues, it demands pragmatic, decisive action.

This article was first published in It's Freezing in LA!, the slow journalism indie magazine on climate change.

Defenders of meat-eating sometimes argue that the problem is ‘intensive’ farming – industrial production on factory farms – and suggest shifting to pasture-fed meat and dairy instead. Few explain that to do so without reducing our meat consumption would require several new planets' worth of land. The fantastic inefficiency of ‘extensively’ farming animals, as George Monbiot has reported eloquently in the Guardian, renders it worse, even, than factory farming. Extensive livestock farming has a higher ecological cost per unit of food by almost every metric, including water use, greenhouse gas emissions, soil loss, and phosphorus and nitrate pollution.

Globally, livestock agriculture accounts for half our total land use, and four fifths of our agricultural land; yet it provides less than a fifth of our calories. Without animal products we could feed the world while reducing global farmland use by more than 75%. Incredibly, this would return to nature an area as large as the US, China, Australia, and the EU combined.

Because this freed-up land could be used to store carbon, the opportunity cost of meat production is enormous, and causes its true carbon footprint to skyrocket. A kilogram of beef protein has a carbon cost of 1250 kg – roughly equivalent to the carbon released by heating an average European home for a year. It's 73 times the carbon cost of sourcing the same protein directly from plants.

These statistics, derived from research first published in Nature and Science in the past few years, reinforce the existing consensus that we must cut our meat and dairy consumption. Though a meat tax will likely remain political anathema for years, this reduction could be achieved incrementally with softer policies. Even limited changes could have outsize impacts: cutting consumption of animal products in half by avoiding the most polluting producers would achieve three quarters of the emissions reductions achieved by going fully plant-based.

If the UK switched entirely to a plant-based diet, meanwhile, the land now used for pasture and feedstock would absorb 150 million tons of CO2 annually – over 40% of current annual emissions. Once we’ve picked the low-hanging fruit of decarbonising the electricity supply, nothing offers comparable reductions in our climate impact. Aviation will not be decarbonised in our lifetimes, and many other sectors – home-heating, private transport, heavy industry – will take decades of investment. We can begin cutting meat from our diets today.

Environmental consciousness is percolating into new segments of society, and increasingly affecting business decisions

Competition will be one major driver of the shift toward plant-based diets. Environmental consciousness is percolating into new segments of society, and increasingly affecting business decisions: investment firm BlackRock’s recent advice against investing in coal is a case in point. According to Sainsbury’s analysis of 2019 consumer spending habits, one in eight Britons is already vegetarian, and by 2025 that number will double; another half of the population will identify as flexitarian. For multinational corporations, the enormous profits on offer matter far more than ethical exigencies.

Moreover, while current plant-based alternatives can rarely compete with the foods they replace on both taste and price, the next generation of products promises to be indistinguishable from animal equivalents at the molecular level. ‘Clean’ or ‘cultured’ meat is already here, though prohibitively expensive to most consumers. Returns on scale and tech-driven increases in efficiency could soon render it commercially viable; one think tank, RethinkX, predicts the collapse of the US dairy and cattle industry by 2030. The fundamental technology enabling this transition, they suggest, will be the programming of micro-organisms such as yeast and bacteria to produce complex organic molecules.

‘Precision fermentation’ is already the source not only of Quorn but also the insulin taken by diabetics, virtually all vitamin C supplements, and the heme protein that gives leading burger alternatives their meaty taste. Dozens of companies are now at work on using it to produce everything from the starch in pasta and crisps to the proteins in ice cream and egg analogues, collagen scaffolds for clean meat, and fats for sustainable palm oil.

Precision fermentation of complex organic molecules has dropped in cost from $1 million per kg in 2000 to $100 per kg today. RethinkX argue that existing technologies will push that cost below $10 by 2025. By 2030, they claim, proteins produced via this process will be five times cheaper than animal equivalents. To ‘disrupt the cow’, precision fermentation need only replicate about 3% of the milk bottle – the key proteins. ‘Industrial cattle farming industry,’ RethinkX predict, ‘will collapse long before we see modern technologies produce the “perfect” cellular steak at a competitive price.’

Between them, the commercial opportunity and the ethical imperative ought eventually to render animal-based foods expensive delicacies at best, like Wagyu beef today.

The genuine difficulties associated with precision fermentation, including that of separating molecules from the bacteria or fungi that produce them, are easy to gloss over. It’s easy too to overestimate the scale of the shift in attitudes so far: globally, plant-based alternatives account for less than 1% of the $1.8 trillion meat market. Growing affluence in developing nations continues to drive year-on-year increases in demand for animal meat, which has not yet peaked.

Nevertheless, this techno-utopian vision of the future of food is compelling. Between them, the commercial opportunity and the ethical imperative ought eventually to render animal-based foods expensive delicacies at best, like Wagyu beef today. If clean meat and dairy products can be produced at a fraction of the cost – financial, ethical, and environmental – of their equivalents, it should become easy to eliminate animals from our diet, and to extend to cows, pigs, and chickens the concern we routinely show for wild animals and domestic pets. What’s uncertain is the pace of this change.

Civil society and the government both have a clear role to play in encouraging the shift towards sustainable diets. Pragmatic, incremental policies within reach include pushing for plant-based options to be available without special request for every public sector meal (30% of meals served), as is already the case in Portugal. Mandating better data collection around the costs of animal food production, including the carbon opportunity costs, could pave the way for an eventual meat tax reflecting the real cost of rearing animals.

Since red meat has been linked to cancer, and plant products generally contain less saturated fat than their animal equivalents, this dietary shift will also deliver a host of ‘co-benefits’. Longer life expectancies, better health, and lower healthcare bills for taxpayers ought to be emphasised, as Dr Carmichael pointed out in his recent report for the CCC UK because they’ll be perceptible long before the benefits of decarbonisation themselves. This report is notable for its debt to behavioural economics and its savvy navigation of the complex politics of meat-eating.

Ours is a transitional moment, perhaps the most important in the history of animal consumption.

Ours is a transitional moment, perhaps the most important in the history of humans eating animals. We slaughter more land animals than ever before – 50 billion every year, most of whom live tragically short lives in needless suffering – but there’s a real possibility of ending factory farming in our lifetimes. The next generation of activists must blend idealism with pragmatism, learning from the successes and failures of past movements, as well as the (often vegan) scientists and entrepreneurs leading the plant-based revolution. Rather than confrontational tactics which risk alienating meat-eaters, they seek to offer better products with wide appeal, and frame behavioural changes as easy, painless, and attractive.

The moral imperative is clear. The Earth’s population is projected to grow by 25% – an additional two billion people – in the next three decades. Massively reducing the amount of meat and dairy in our diets is the only way to feed everyone, reduce the carbon footprint of agriculture, and return to nature the land desperately needed to offset greenhouse gas emissions as well as protect ecosystems at risk.

IFLA! is a critically acclaimed independent magazine with a fresh take on climate change. Printed bi-annually, we find the ground between science and activism, inviting writers and illustrators from a variety of fields to give us their view on how climate change will affect — and is affecting — society. Discover more writing, subscribe to the beautiful print piece, or sign up for one of their events at itsfreezinginla.co.uk

Aron Penczu is a writer, filmmaker and educator. Born in Hungary, he grew up internationally and came to the UK to study literature at Cambridge. He has been (mostly) plant-based since 2016.

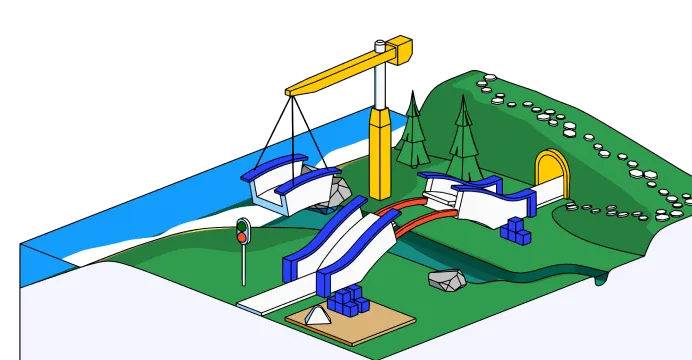

Joey Yu is an illustrator/animator living in London, creating imagery for clients including The New York Times, The Guardian, Tate or Hermes. She's lived in Seoul, Korea and Trancoso, Brazil.